| (11 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The term reasonable is an interesting one because it depends on the individual and has within itself logical contradiction. On this site, | The term reasonable is an interesting one because it depends on the individual and has within itself logical contradiction. On this site, articles aim to be reason-ABLE, which basically means that if there is new information or principles discovered they can be used to revise a past view in favor of one that is more complete, though not absolute. The principle, as a friend once said, is this: show me your strength, and I will show you your weakness. | ||

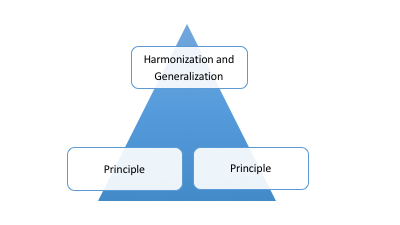

This strength/weakness concept applies to ideologies which are ultimately based on a REASON-able process each of which seems to have its own inherent weaknesses that adherents are largely blind to until they grow. This concept is further illustrated with triangle with two principles at its base and one generalized principle or harmonization at its peak. [[File:Reasoning_Process_Principle_Triangle.png|right|400px]] | |||

A similar principle is at work when considering an event and the facts which help shape the narrative of that event. Consider that two children with the same set of parents may have a vastly different views of those parents as well as outcomes. In the same way, it is seen that an event is based upon a description or recollection of smaller events that happened - which contain information about the location of objects during each of the smaller events as well as the actors that participated in the event. If one's view of the full picture is obscured by either one's own limitations or some other reality that prevents capturing the whole story, then we find that one small detail, if overlooked, can often result in a dramatically different understanding of that event. | |||

Stated simply, until one knows everything, one knows nothing - but until one knows everything, one can try to do the best he can with what he has. | |||

Consider the following: | |||

*[[A Compilation of I-did-not-know-thats (IDNKT)]] | |||

*[[Strengths and Weaknesses of Various Ideologies]] | |||

*[[What Changed their Minds]] | |||

==Is Reasoning itself, Reason-able?== | |||

Spock said, paraphrasing, logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end. Perhaps we must apply some reasoning to our reasoning. Eventually, we may come to realize that reasoning itself becomes defeated as the sole mechanism for obtaining [[Truth]] and getting beyond our individual [[Arguing with Loki|divided perspectives]]. | |||

==The Foundation of Reasoning - the Senses== | |||

Consider seeing four *things*, and from this abstracting the concept of four. Similarly, we've seen things with certain properties, and abstracted from them, then abstracted from those abstractions to get more complicated abstractions such as "pi". But it all, ultimately, goes back to the level of the senses. | |||

We have seen lines, and we've observed that they have certain properties. The closer the lines are to being "perfect", the more closely they have certain properties we like. If you consider two planes in three-dimensional space, the closer they are to "perfectly" flat and parallel to each other, the further along them you have to travel before they intersect (or reach a certain level of divergence, or whatever). "Plane" is a valid concept, regardless of whether you can get a "perfect" plane in reality, and it's abstracted from observing planes. | |||

Other concepts, of which one may not have observed a referent, are still derived from the senses. If one derives such concepts as "angle" and "pentagon" and "polyhedron" (or even "3D shape"), one can derive the concept "dodecahedron" by thinking through how pentagons make faces of 3D shapes, thinking through the logic of how they fit together, etc. | |||

Whatever the particular details, it always, all of it, ultimately goes back to the senses. That "ultimately" may be a long chain, and the base of it in one's mind impossible to trace back to for any particular concept -- it could be an immensely large number of things one has observed, which one has abstracted from, and built abstractions on top of those abstractions from, and so on. | |||

Latest revision as of 12:06, 25 July 2017

The term reasonable is an interesting one because it depends on the individual and has within itself logical contradiction. On this site, articles aim to be reason-ABLE, which basically means that if there is new information or principles discovered they can be used to revise a past view in favor of one that is more complete, though not absolute. The principle, as a friend once said, is this: show me your strength, and I will show you your weakness.

This strength/weakness concept applies to ideologies which are ultimately based on a REASON-able process each of which seems to have its own inherent weaknesses that adherents are largely blind to until they grow. This concept is further illustrated with triangle with two principles at its base and one generalized principle or harmonization at its peak.

A similar principle is at work when considering an event and the facts which help shape the narrative of that event. Consider that two children with the same set of parents may have a vastly different views of those parents as well as outcomes. In the same way, it is seen that an event is based upon a description or recollection of smaller events that happened - which contain information about the location of objects during each of the smaller events as well as the actors that participated in the event. If one's view of the full picture is obscured by either one's own limitations or some other reality that prevents capturing the whole story, then we find that one small detail, if overlooked, can often result in a dramatically different understanding of that event.

Stated simply, until one knows everything, one knows nothing - but until one knows everything, one can try to do the best he can with what he has.

Consider the following:

- A Compilation of I-did-not-know-thats (IDNKT)

- Strengths and Weaknesses of Various Ideologies

- What Changed their Minds

Is Reasoning itself, Reason-able?

Spock said, paraphrasing, logic is the beginning of wisdom, not the end. Perhaps we must apply some reasoning to our reasoning. Eventually, we may come to realize that reasoning itself becomes defeated as the sole mechanism for obtaining Truth and getting beyond our individual divided perspectives.

The Foundation of Reasoning - the Senses

Consider seeing four *things*, and from this abstracting the concept of four. Similarly, we've seen things with certain properties, and abstracted from them, then abstracted from those abstractions to get more complicated abstractions such as "pi". But it all, ultimately, goes back to the level of the senses.

We have seen lines, and we've observed that they have certain properties. The closer the lines are to being "perfect", the more closely they have certain properties we like. If you consider two planes in three-dimensional space, the closer they are to "perfectly" flat and parallel to each other, the further along them you have to travel before they intersect (or reach a certain level of divergence, or whatever). "Plane" is a valid concept, regardless of whether you can get a "perfect" plane in reality, and it's abstracted from observing planes.

Other concepts, of which one may not have observed a referent, are still derived from the senses. If one derives such concepts as "angle" and "pentagon" and "polyhedron" (or even "3D shape"), one can derive the concept "dodecahedron" by thinking through how pentagons make faces of 3D shapes, thinking through the logic of how they fit together, etc.

Whatever the particular details, it always, all of it, ultimately goes back to the senses. That "ultimately" may be a long chain, and the base of it in one's mind impossible to trace back to for any particular concept -- it could be an immensely large number of things one has observed, which one has abstracted from, and built abstractions on top of those abstractions from, and so on.